The “Sunday Night Insomnia” Effect: Why Weekends Break Your Sleep

You sleep reasonably well from Monday to Friday, but when Sunday night arrives, sleep suddenly disappears. You feel tired, you want to sleep, yet your mind stays alert, your body refuses to relax, and the clock keeps moving forward.

This experience is so common that sleep researchers have a name for it: the “Sunday Night Insomnia” effect. It is not random bad luck. It is the predictable result of how weekends quietly disrupt your biological clock, your sleep pressure, and your mental state.

Quick navigation

What is the “Sunday Night Insomnia” effect?

Sunday night insomnia describes difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep on Sunday evenings, often despite sleeping relatively well on work nights. People usually report:

- Feeling sleepy but mentally alert on Sunday night

- Lying in bed thinking about the upcoming week

- Going to bed “on time” but not falling asleep

- Waking up frequently or too early on Monday morning

This pattern is strongly linked to weekend schedule shifts and to anticipatory stress about the workweek. Researchers often group it under the broader concept of social jet lag, a mismatch between your biological clock and your social obligations.1–3

Social jet lag: how weekends break your body clock

During the workweek, most people wake up at a fixed time due to jobs, school, or responsibilities. On weekends, alarms disappear, bedtimes drift later, and mornings start later. This feels harmless, but biologically it matters.

What is social jet lag?

Social jet lag refers to the difference between your sleep timing on workdays and free days. It mimics the effects of traveling across time zones without actually moving. Studies show that many adults experience 1–3 hours of social jet lag every weekend.1,2

- Friday & Saturday bedtime shifts later

- Sleeping in to “catch up”

- Reduced morning light exposure

- Later meals, caffeine, and alcohol intake

By Sunday evening, your internal clock is no longer aligned with Monday morning expectations. Your brain thinks it is still in a later time zone.

Why sleeping in backfires

Sleep pressure builds the longer you stay awake. When you sleep late on Sunday morning, you reduce that pressure. At the same time, late-night light exposure on Friday and Saturday delays your circadian rhythm.

The result is a double hit:

- Not enough sleep pressure to fall asleep early

- A delayed internal clock telling your brain it is not bedtime yet

Research shows that social jet lag is associated with poorer sleep quality, increased fatigue, and higher risk of metabolic and mood problems over time.1–3

What happens inside your brain & hormones

Sunday night insomnia is not “in your head” in a dismissive sense. It has measurable biological drivers.

Melatonin timing gets delayed

Melatonin is a hormone that signals darkness and sleep readiness. Late bedtimes, screens, and reduced morning light on weekends delay melatonin release. When Sunday night comes, melatonin may not rise until much later than usual.4,5

Cortisol rises with anticipatory stress

Cortisol is a stress hormone that naturally rises in the morning to help you wake up. Anticipating Monday responsibilities can raise evening cortisol levels, making it harder to fall asleep. Studies link work-related stress and rumination to delayed sleep onset and poorer sleep efficiency.6,7

Sleep pressure is weaker

The homeostatic drive for sleep depends on how long you have been awake. Sleeping in on weekends weakens that drive, making Sunday night feel “wired but tired.”

Why Sunday anxiety keeps your mind awake

Beyond biology, Sundays often carry a psychological load. Research on pre-sleep cognition shows that worry, planning, and rumination significantly delay sleep onset.6–8

Common Sunday thought patterns include:

- Mentally rehearsing the upcoming workweek

- Worrying about unfinished tasks

- Anticipating conflict or pressure

- Feeling regret about an unproductive weekend

This mental activity activates the nervous system, keeping the brain in problem-solving mode rather than sleep mode.

How to fix Sunday night insomnia (step by step)

The solution is not to force sleep, but to gently realign your clock and calm your mind before Sunday night arrives.

Step 1: Protect your wake-up time

Instead of sleeping in for hours, limit weekend wake-up time to within 60–90 minutes of your weekday schedule. Research suggests this significantly reduces social jet lag while still allowing some recovery sleep.1,2

Step 2: Use morning light strategically

Get bright light exposure within the first hour of waking on Saturday and Sunday. Natural daylight is best. Morning light anchors your circadian rhythm and counteracts weekend delay.4,5

Step 3: Avoid late Sunday naps

Late afternoon or evening naps reduce sleep pressure and make Sunday night insomnia more likely. If you must nap, keep it under 30 minutes and before mid-afternoon.

Step 4: Create a “Sunday shutdown ritual”

Studies on cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) show that structured wind-down routines reduce pre-sleep arousal.8,9

- Write a short plan for Monday

- List unresolved worries and set a time to address them

- Dim lights earlier than usual

- Disconnect from work-related content

Step 5: Keep Sunday evening calm & predictable

Large meals, alcohol, and intense stimulation on Sunday night worsen sleep. Treat Sunday evening like a “soft landing” rather than a mini Saturday night.

Amazon tools that support a smoother Sunday night

These tools do not fix Sunday night insomnia alone, but they support the strategies above. Each product category aligns with evidence-based sleep principles.

- Simulates natural morning light on weekends

- Helps stabilize wake time and circadian rhythm

- Useful during darker seasons

- Provides bright light for circadian alignment

- Helpful when outdoor light is limited

- Supports earlier melatonin onset at night

- Helps unload worries before bed

- Reduces rumination and mental arousal

- Supports consistent Sunday rituals

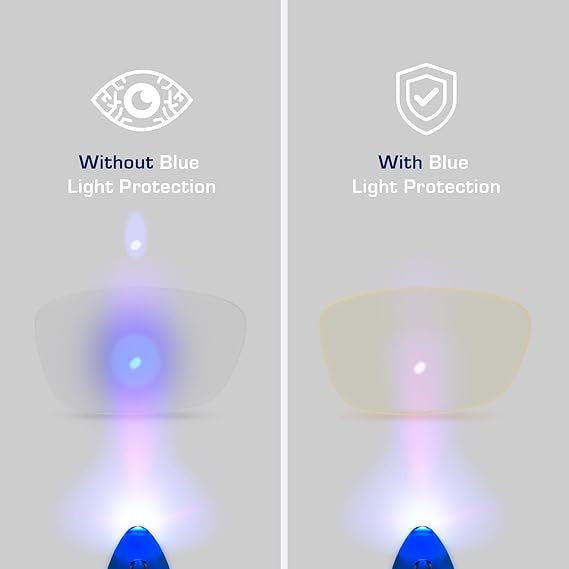

- Reduce circadian delay from screens

- Support earlier melatonin release

- Useful on Sunday evenings

FAQ

Q: Is Sunday night insomnia a medical disorder?

A: No. It is a common sleep pattern linked to social jet lag and anticipatory stress. However, if it occurs alongside chronic insomnia symptoms, professional evaluation is recommended.

Q: Should I go to bed earlier on Sunday?

A: Going to bed earlier without adjusting wake time and light exposure usually fails. Focus first on consistent wake-up times and calming routines.

Q: Does this mean I should not enjoy weekends?

A: No. The goal is moderation, not deprivation. Small schedule shifts are fine; large ones cause problems.

Conclusion

Sunday night insomnia is not a mystery and not a personal failure. It is the predictable result of how weekends disrupt sleep timing, light exposure, and mental state.

By reducing social jet lag, anchoring wake-up times, using morning light, and creating a calm Sunday evening routine, you can significantly improve how easily you fall asleep and how rested you feel on Monday.

Fixing Sunday night sleep is one of the highest-impact changes you can make for your weekly energy, mood, and long-term health.

Disclaimer

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not provide medical advice. It is not a substitute for consultation with a qualified healthcare professional. We are not responsible for any decisions made based on this content.

Scientific references

- Wittmann M, et al. Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiology International. 2006. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16687322/

- Roenneberg T, et al. Circadian rhythms, sleep, and the menstrual cycle 2007. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17383933/

- Parsons MJ, et al. Social jetlag, obesity and metabolic disorder. Current Biology. 2015. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25601363/

- Gooley JJ, et al. Exposure to room light before bedtime suppresses melatonin. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2011. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21193540/

- Khalsa SBS, et al. A phase response curve to light in humans. Journal of Physiology. 2003. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12717008/

- Åkerstedt T, et al. Disturbed sleep in relation to stress and work. Biological Psychology. 2002. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12217447/

- Brosschot JF, et al. Worry, stress and sleep. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006.

- Harvey AG. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2002. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12186352/

- Edinger JD, Means MK. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15951083/