Revenge Bedtime Procrastination: Why You Delay Sleep and How to Stop

It is late, you are exhausted, and you know you should be asleep. Yet instead of turning off the light, you keep scrolling, watching “just one more” episode, or finally enjoying quiet time that you did not get during the day. You are not alone – this pattern has a name: revenge bedtime procrastination.

Revenge bedtime procrastination means choosing to delay sleep on purpose, even when you know you will be tired tomorrow, in order to reclaim a sense of freedom, pleasure, or control after an overloaded day. Over time it can seriously damage deep sleep, mood, metabolism, and overall health.

Quick navigation

- What is revenge bedtime procrastination?

- Why you do it (psychology & self-control)

- The real costs for your brain, body, and mood

- Step-by-step plan to break the cycle

- Amazon tools that support better evenings (max 5)

- A real-life style story you may recognize

- FAQ

- Conclusion

- Disclaimer

- Scientific references

What is revenge bedtime procrastination?

Psychologists first described bedtime procrastination as failing to go to bed at the intended time even though there are no external reasons preventing it – and found that it was strongly linked to insufficient sleep and daytime fatigue.1,2 Later, the term “revenge bedtime procrastination” emerged to capture a more specific pattern: people stay up late not because they forget the time, but as a form of “revenge” against a day that felt too controlled or stressful.

Typical signs that what you experience is revenge bedtime procrastination:

- You often think or say, “It is my only time for myself” at night.

- You continue watching, scrolling, or gaming even while feeling very sleepy.

- You know tomorrow will be harder, but the desire for freedom now wins.

- Your bedtime is much later than you intend, especially compared to your wake time.

This is not simple laziness. It is usually a sign that your days feel overloaded, your boundaries are weak, or you lack satisfying breaks – so your brain tries to “reclaim” time late at night, even at the cost of sleep.

Why you delay sleep: psychology & self-control

Research on bedtime procrastination shows it is closely tied to self-regulation – the ability to align your actions with your long-term goals rather than short-term impulses.1,3 When your self-regulation is depleted or overwhelmed, immediate rewards (checking social media, watching a show) feel more appealing than going to bed for the sake of tomorrow’s energy.

1. Long days drain your self-control “battery”

Throughout the day, you may be:

- Following other people’s schedules.

- Taking care of work, children, or relatives.

- Handling emails, messages, and constant requests.

By evening, your mental energy for self-control is low. Research suggests that people with lower self-regulation scores report more bedtime procrastination and inadequate sleep, even when they logically know sleep is important.1,3 The brain chooses short-term comfort over long-term health.

2. Devices are designed to keep you engaged

Streaming platforms and social media are built around endless feeds, autoplay, and notifications that encourage “just a bit more.” Studies on electronic media use show that higher screen time – especially close to bedtime – is associated with shorter sleep duration, delayed bedtimes, and poorer sleep quality across age groups.4–7

In other words, you are not simply weak; you are playing against systems that are engineered to grab your attention when your self-control is already tired.

3. You feel a lack of control over your day

A core emotional driver of revenge bedtime procrastination is autonomy: the feeling that your time belongs to you. If the whole day feels like it belongs to others, the late evening becomes the only place you feel free. Staying up becomes an act of quiet rebellion: “They took my day; they will not take my evening.”

4. Night offers emotional escape

For some, the night is not only about entertainment but also emotional escape – avoiding difficult thoughts, loneliness, or stress. Digital media use is closely linked to mood and mental health, and some people use late-night scrolling as a temporary numbing strategy.4,6 The problem: it steals the sleep that would actually help the brain process emotions in healthier ways.

The real costs: how revenge bedtime procrastination hurts your body & brain

Regularly sacrificing sleep for late-night “revenge” time is not harmless. Chronic insufficient sleep is associated with:

- Impaired focus and memory – making work and learning harder.8

- Increased risk of anxiety and depression – poor sleep disrupts brain circuits involved in emotion regulation.8,9

- Higher risk of weight gain and metabolic problems – short sleep is linked to altered appetite hormones and higher risk of type 2 diabetes.8

- Cardiovascular strain – consistently short sleep duration is associated with elevated blood pressure and higher cardiovascular risk.8

- Weakened immune function – making it harder for your body to fight infections.8,9

Expert panels reviewing the evidence conclude that most adults need at least 7 hours of sleep per night on a regular basis for optimal health and functioning.8 When bedtime procrastination regularly cuts that down, your “revenge” ends up hurting only you.

A step-by-step plan to stop revenge bedtime procrastination

You cannot fix revenge bedtime procrastination with willpower alone. You need to change both the structure of your day and the design of your evenings, and make it easier for your tired brain to choose sleep.

Step 1: Redesign your day so you do not feel starved for “me time”

If your only personal time is between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m., of course you will cling to it. Try to insert small pockets of autonomy earlier:

- Schedule one small enjoyable activity during the day (a short walk, a book chapter, a mindful coffee, a brief hobby session).

- Set simple boundaries where possible: protect one block of time as “no work, no requests.”

- Communicate with family or housemates about your need for 15–30 minutes of uninterrupted downtime before the late evening.

Psychologically, when your brain knows it will get small doses of pleasure and autonomy earlier, the urge to “steal” hours from sleep becomes weaker.

Step 2: Create a tech boundary you can actually keep

Instead of promising yourself “no phone after 8 p.m.” (and then breaking it), set a realistic boundary that fits your life:

- Choose a digital sunset time – for example, 45–60 minutes before your intended sleep time.

- Move the most tempting devices away from the bed – ideally out of the bedroom or at least across the room.

- Turn off autoplay and disable non-essential notifications in the evening.

Large studies show that higher evening screen use, especially in bed, is associated with shorter sleep duration, more bedtime procrastination, and more insomnia symptoms.4–7 You do not have to eliminate screens completely, but shifting the most intense use earlier and reducing it in the last hour helps your brain wind down.

Step 3: Replace “doom scrolling” with a pre-planned wind-down ritual

People procrastinate less when their next action is clear and simple. Plan a short, repeatable evening ritual that signals “now we transition toward sleep.” For example:

- Dim the lights 60 minutes before bed.

- Make a caffeine-free herbal tea.

- Write down three things you accomplished and three things you can handle tomorrow.

- Read a physical book or do light stretching for 15–20 minutes.

- Practice a simple breathing exercise (for example, slow 4–6 breaths per minute).

Clinical reviews of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) show that structured routines, stimulus control (using bed only for sleep and intimacy), and relaxation strategies lead to meaningful improvements in sleep onset, total sleep time, and sleep efficiency, with durable long-term effects.10–12 You are borrowing a simplified version of those principles for your own evenings.

Step 4: Make sleep the default, not the decision

When you are tired at the end of the day, decisions feel harder. The more choices you have in the evening, the easier it is to postpone sleep. Try to:

- Set a consistent target bedtime and wake time (even on weekends) to stabilize your body clock.

- Set an alarm not just for waking, but also a “get ready for bed” reminder 45–60 minutes before sleep.

- Lay out sleepwear, prepare your bedroom, and pre-fill your water or tea earlier in the evening.

- Charge your phone away from the bed so that staying up means physically getting up – increasing friction.

The goal is for sleep to become the path of least resistance, while staying up requires extra steps.

Step 5: Work with your thoughts, not against them

Blaming yourself (“I am so weak”) usually makes the problem worse. Instead, notice and reframe thoughts like:

- “It is my only time to relax.” → “Real rest comes from sleep. I can build small relaxing moments into my day.”

- “One episode will not hurt.” → “Every extra 30 minutes I stay up is 30 minutes less sleep my body needs.”

- “I will just scroll for five minutes.” → “If I start scrolling now, it will likely be 30–60 minutes. I can put the phone in the other room instead.”

CBT-I research shows that changing how you respond to unhelpful thoughts – rather than trying to force them to disappear – is a powerful way to improve sleep without medication.10–12

Amazon tools that support healthier evenings

You do not need products to fix revenge bedtime procrastination, but certain tools can make the new habits easier to follow.

- Designed to filter a portion of blue light from phones, tablets, and laptops in the evening.

- Helpful if you must use devices at night but want to minimize their impact on your sleep timing.

- Pairs well with a digital “curfew” to reduce eye strain and support melatonin rhythms.

- Provides simple prompts to review your day, list worries, and plan tomorrow before bed.

- Helps offload racing thoughts so your mind does not feel obligated to process everything at midnight.

- Supports the CBT-I principle of scheduling “worry time” earlier, not in bed.

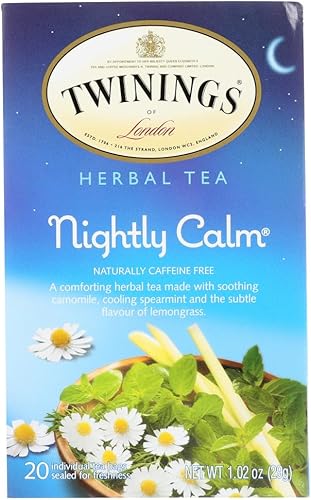

- Typically combines herbs like chamomile, lemon balm, or passionflower known for calming properties.

- Creating a small tea ritual signals to your brain that the day is ending.

- Pairs well with dimmed lights and reading a physical book instead of scrolling.

- Blocks ambient light from streetlights, sunrise, or electronics that might tempt late-night scrolling.

- Contoured designs reduce pressure on eyes while keeping things dark.

- Useful if blackout curtains are not an option or you share a room.

- Allows you to diffuse calming scents like lavender or bergamot in the evening.

- Helps you associate the bedroom with calm, offline relaxation instead of stimulation.

- Can be set on a timer so it becomes part of a predictable wind-down cue.

A story you might recognize (composite example)

Consider a composite example inspired by many real professionals. “Alex” is a 38-year-old marketing manager. Her days are back-to-back meetings, messages, and family responsibilities. By the time her children are in bed and the kitchen is cleaned, it is already 10:30 p.m.

Alex knows she should go to bed by 11 p.m. to feel good at her 6:30 a.m. alarm. Instead, she collapses on the couch, opens a streaming app, and starts “just one episode.” Autoplay kicks in. Her phone buzzes. She checks social media, scrolls through news, and before she knows it, it is 1:30 a.m.

The next day she feels foggy, anxious, and guilty – and promises herself she will go to bed early tonight. But when night comes, she feels that same urge to reclaim time. The cycle repeats.

When Alex finally decides to change, she:

- Plans a 20-minute walk and a 10-minute coffee break alone during the day as personal time.

- Sets an 11 p.m. “lights out” goal and a 10 p.m. alarm that says “offline & wind down.”

- Moves her phone charger to the hallway and reads a paperback novel in bed.

- Uses a simple herbal tea and diffuser as cues that the evening is closing.

At first, she still feels the pull to keep watching, but after a couple of weeks, her new routine feels more automatic. She falls asleep closer to 11 p.m., wakes up more refreshed, and notices her mood stabilizing. Her “revenge” shifts from stealing hours from sleep to intentionally protecting sleep as an act of self-respect.

FAQ

Q: Is revenge bedtime procrastination a real diagnosis?

A: No. It is not a formal psychiatric or medical diagnosis, but it describes a pattern that many people experience: deliberately staying up late to reclaim free time, despite knowing it will reduce sleep. Researchers study it under the broader concept of bedtime procrastination and self-regulation.

Q: Do I have to give up all screens at night?

A: Not necessarily. The key is to reduce stimulating, emotionally intense, or endless scrolling close to bedtime. Moving your heaviest screen use earlier in the evening, setting a digital “cutoff” time, and using dimmer, warmer light can already make a big difference.

Q: How long will it take to see changes?

A: Many people feel a difference in energy and mood within 1–2 weeks of more consistent sleep. For deeper habit change, think in terms of several weeks of steady practice. Research on CBT-I shows that behavioral and cognitive changes can keep improving sleep long after formal treatment ends.10–12

Q: When should I seek professional help?

A: If you regularly sleep less than 6 hours, feel severely tired during the day, experience loud snoring, gasping, or breathing pauses in sleep, or have significant anxiety or depression, it is important to talk with a healthcare professional or sleep specialist. They can rule out conditions like insomnia disorder, sleep apnea, or mood disorders and recommend evidence-based treatments.

Q: Is cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) helpful for this?

A: CBT-I is considered a first-line treatment for chronic insomnia and has strong evidence for improving sleep onset, total sleep time, and sleep quality in different groups.10–12 While revenge bedtime procrastination has a specific motivational flavor, many of the same CBT-I tools (stimulus control, sleep scheduling, cognitive restructuring) can be adapted to help break the pattern.

Conclusion

Revenge bedtime procrastination is a modern trap: you sacrifice tonight’s sleep to reclaim the free time you feel was stolen by the day. It is understandable and deeply human – but over time it drains your energy, harms your health, and makes tomorrow’s stress even harder to handle.

Science shows that bedtime procrastination is closely tied to self-regulation and the way we manage our time, devices, and emotions.1–3,4–7 The solution is not to shame yourself into “more discipline,” but to redesign your environment and routines so that sleep becomes the easy, natural choice.

By:

- Building small moments of “me time” into the day,

- Setting realistic tech boundaries in the evening,

- Creating a simple wind-down ritual that your brain recognizes,

- Protecting a consistent sleep window most nights,

- And using supportive tools – from journals to sleep masks – when helpful,

you can gradually shift from revenge to restoration. Your evenings can still include pleasure and autonomy – but not at the expense of the deep sleep that makes everything else work better.

Disclaimer

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. It is not a substitute for consultation with a qualified healthcare professional. Always speak with your doctor or another licensed health provider about your personal health, sleep problems, medications, or before making significant lifestyle changes.

We do not accept responsibility for any decisions you make or actions you take based on the information in this article or for any consequences that may result from their use.

Scientific references

- Kroese FM, Evers C, Adriaanse MA, de Ridder DTD. Bedtime procrastination: introducing a new area of procrastination. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:611. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00611/full

- Kroese FM, et al. Bedtime procrastination: a self-regulation perspective on sleep insufficiency in the general population. Health Psychology. 2016;35(8):835–844. Abstract at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24997168/

- Kroese FM, de Ridder DTD, Evers C, Adriaanse MA. Bedtime procrastination and self-regulation: a research overview. Accessed via: https://www.academia.edu/20838600/Bedtime_procrastination_introducing_a_new_area_of_procrastination

- Han X, et al. Electronic media use and sleep quality: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2024;15:1159221. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11077410/

- Brautsch LAS, et al. Digital media use and sleep in late adolescence. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2023;69:101809. Abstract at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1087079222001551

- Fiore M, et al. Electronic media use and sleep in children and adolescents: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(10):5290. Abstract at: https://www.springermedizin.de/electronic-media-use-and-sleep-in-children-and-adolescents-in-we/19710454

- National Sleep Foundation. Recommended sleep durations by age: scientific background summarized in: Watson NF, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: a joint consensus statement. Sleep. 2015;38(6):843–844. Full text at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4442216/

- Altena E, et al. Mechanisms of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia. Journal of Sleep Research. 2023;32(6):e13860. Abstract at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jsr.13860

- Rossman J. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: an effective and underutilized treatment for insomnia. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2019;13(6):544–547. Full text at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6796223/

- Mei Z, et al. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health. 2024;12:1413694. Full text at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1413694/full